Poet. Journal writer. Image-maker. These are just a few of the creative guises I slipped into as I embarked on an inward journey in search of my newest set of fictional characters.

What I hungered to discover was what is truthful and powerful in my own world view. Once I unearthed that profound truth, I wanted to know how best I could weave it into a story through memorable characters.

With this lofty goal in mind, I signed up for Image Journaling: Creative Renewal and the Inward Journey©, a course and forthcoming book by master artist Constance Pierce.

Pierce believes “the language of imagery” holds the key to an author’s inner life. She combines the creative processes of image-making with journal writing, helping participants set off on an inward journey.

“I use unconventional approaches with a variety of media to prompt and empower the writing in surprising ways,” Pierce said. “The unexpected atmospheres and archetypes that arise often suggest narratives, sequences, and characters that one might not conjure through self-will alone.”

My first assignment was to think about creating a writing invocation. Pierce described the invocation as a “calling out to something or someone greater than yourself to companion you as you embark on your new creative quest.”

She said this could be “a letter, a litany, a parable or allegory, or even a chorus of inner voices, speaking to each other for the first time—any word form you imagine and choose.”

What it must be, however, is authentic.

“The one requirement is that it should honestly emerge from where you are right now,” Pierce said.

For me, my invocation materialized as a petition. Though I struggled at first, I soon dug deep into discerning what is important to me with my writing and what I hope to achieve with each written piece.

I titled my petition “Call of the Storyteller” and wrote:

Reveal to me a tale only I can tell, one steeped in the writing wisdom I have earned.

Make me not so much wrestle with words as worry over meaning.

Teach me to listen for the sounds of my story awakening…of its characters unfolding…of their lives intersecting.

Share with me the grace to give voice to those who have none.

Help me approach this work with ease and excitement. No struggling over sentences, no fear of the unknown.

Just me, writing the story I must write — bold and determined;

an adventurer striking out through the landscape of my imagination.

This has now become a mantra for me, holding both power and permission. I refer to it before beginning any new writing project.

From there, Pierce guided us in experimenting with simple abstract monoprint mark-making, improvising with fluid watercolors and iridescent acrylic paints that enhanced our prints. (Author’s note: View a Flickr collection of various monoprints and “Image Journals” created in one of Pierce’s classes.)

“This process of image-releasing and image-nurturing is often as advantageous to writers as it is to visual creatives,” Pierce said. “Part soul-work and part storytelling, the process encourages images to surface from memory and imagination. This process may also illuminate our inner life in fresh ways and unleash untried powers of self-expression.”

This proved true for me as I made the time to sit with the images I’d created. Pierce suggested reserving space on an art table for a “quiet, contemplative reservoir,” giving the images respect and attention. Once I did that, a volley of ideas came to mind. We then added words alongside the monoprints, using a variety of media, which amped up my creativity.

“We play with words as visual elements,” Pierce said. “What one writes with will often change the content of what one writes. We explore this in depth by alternating fine point pens with brush, writing in watercolors or bleeding inks, colored pencils, wax-resist, or layering altered photo images with word-transparencies. Words and images conjoin. It’s often startling what content comes forth.”

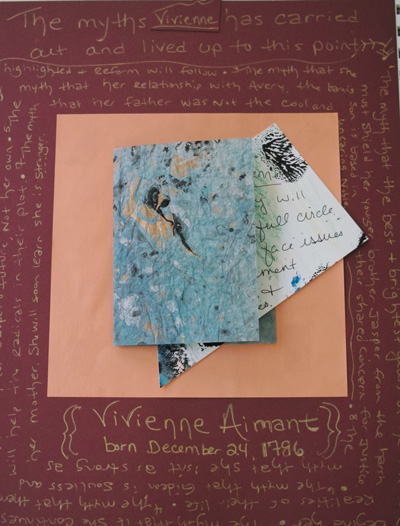

For me, the most powerful moments came when I considered the myths that Vivienne, one of my main characters, has embraced and lived up to this point in her life. I began by choosing a piece of a monoprint that had edges of darkness that moved inward to light at the center.

Affixing the print to a small sheet of textured gold/blue paper so that it was hidden by a flap that could be lifted, I wrote my hope for her story. Using a gold gel pen on a dark background, I began writing about the myths she’s embraced. I wrote from one corner of the page to another, around and around, her story flowing out of me. So much conflict and drama were embedded in those myths! But I wouldn’t have thought about them so thoroughly if not for the “Image Journal” process.

I also created two letters of forgiveness—for a story I hadn’t yet fleshed out, about characters I’d only begun to consider. In those letters, their internal conflict was born.

“Though the image-making explorations prompt us into creation, it is the written words of the initial invocation composed in simple pen or pencil that charge the whole process with a profound energy,” Pierce explained.

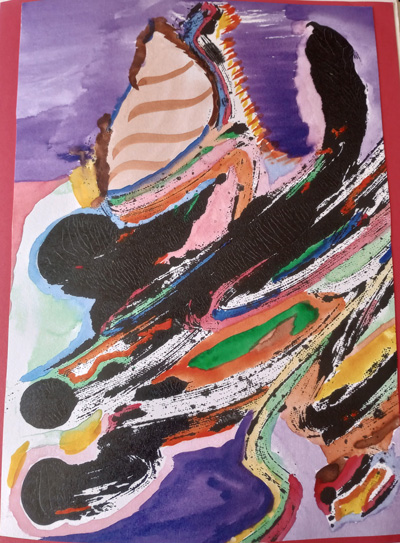

Another moving moment was finding what appeared to be to be a Viking’s longship tossed about on a turbulent sea. This would belong to one of the characters whose story came out of the “two letters of forgiveness.” Serendipity! Seeing the image led to a torrent of words, which became the beginning of this character’s story.

The beauty of this method is that there is no timeframe for being done with the creativity.

“The ‘Imaging Journal’ flourishes in a non-linear manner,” Pierce said. “At times we start the book in two or more places accompanied by a huge leap of faith. The stew pot of seemingly disparate elements sort themselves out and find their rightful places as we venture on. Time is as much a part of the process as the page, the pen, or the brush.”

While not every writer can enjoy in-person instruction with Pierce as their guide, the following suggestions might help you create a few pages of your own “Image Journal:”

- Create a worktable with two areas, one where artistic chaos reigns and the other where you place your most compelling pieces and contemplate them.

- Experiment on the page with regular and metallic watercolors, gel pens, colored pencils, and blue/gold marble decorative paper.

- For any monoprints you create, look for the suggestions of figures (human, animal, tree form, plant form) and use these vertically. Horizontally is where you will find landscapes.

- Meditate and then respond and write about the presence of an image.

- Remember that when an image can be seen in more than one way, it creates mystery.

- Variety is key.

- Place dominant images on the right-side of your journal page. On the left side, put journaling or tiny images surrounded by vastness. Don’t overcrowd the page.

- Be brave and cultivate a beginner’s mindset. Most of all, have fun!

________________________

Lindsay Randall is the author of historical and contemporary romances. This article is from the February 2024 edition of Nink,

Master artist and former professor Constance Pierce has taught variations of her “Image Journal” materials at The Yale Divinity School, The Smithsonian Institution’s Campus on the Mall, Ursuline College Master of Arts in Counseling and Art Therapy Program, The Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and others. She has exhibited nationally in the United States, as well as in Europe and Japan.